From the archives: The unbelievable life of one very old dog

In 2020, we said goodbye to Shiva, our Blue Heeler who had been with me or my ex-husband or someone in my family for 15 of her 17 years.

Editor’s note: As readers know, I occasionally republish older posts from The Feminist Kitchen archive, which goes back to 2010, when it started as a WordPress blog. This post was one of my final posts on that platform, published on Sept. 27, 2020, under the headline: “We can do hard things: Pet loss and grief in the time of COVID-19.” Tomorrow, I have a follow-up to this post about how we’ve filled the dog-shaped void.

We've been in mourning this week.

On Thursday, we said goodbye to Shiva, a family dog who was part of my life before I had my own family.

My kids, ages 13 and 10, and my boyfriend and I gathered around her as she lay in the grass enjoying one last quiet morning while the kind vet explained the process of putting her to sleep. We were at Frank's house, one of half a dozen places she would call home over her life.

It was a farewell I'd been dreading for years. At 17, she had been in a slow decline for years, but I remember when she was a lively 2-year-old, dragging sticks three times her length out of any creek bed she could find.

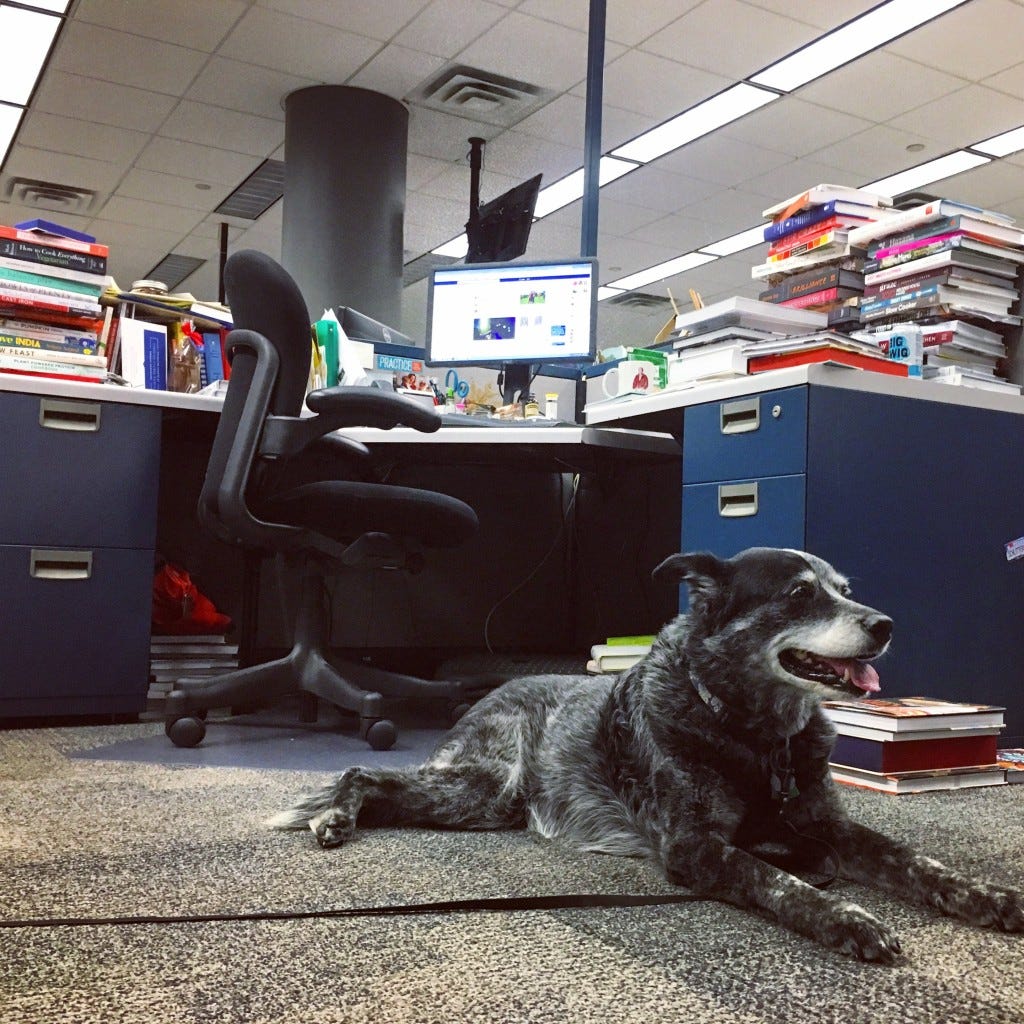

Way back before kids, before the divorce, before the food job, before my dad suffered through his final months, Shiva found her way into the care of Ian, my ex-husband. It was the summer of 2005, just a few weeks before we met, and a friend of his had found her at an abandoned house, or so the story goes. I was interning at Texas Monthly, and he'd just moved to Austin from Canada. He was a cat person who said he'd never get a dog, and then Shiva rolled in, more pepper than salt and with a strong herding instinct.

When my best friend died the following year and I was newly pregnant and completely unaware of it, Shiva was there as I tried to find meaning in life after a traumatic loss. I was grieving Troy, but soon, I was grieving the death of my singleton life where I didn't have to worry about raising another human. I also carried a deep sadness that I was enmeshed in such an unhealthy relationship, but we persevered and started a family: Ian, me, Julian, and Shiva.

Not working through my grief and codependency at that time meant I trudged onward, managing, mothering, fixing, and figuring out any problem that came up. But Shiva wasn't a problem I had to solve. She was a steady constant. A predictable force during an unpredictable time.

Shiva took quickly to baby Julian, licking his face and eating any scraps of food that fell on the floor. But after he started toddling over her and pestering her like a little sister, Shiva needed some extra space.

My parents had just put down my childhood dog, Bernie, and offered to take Shiva in while we focused on being new parents. We met in Oklahoma one weekend in early 2009 and made the switch. Shiva would be their dog for the next 8 years, thriving in my small hometown in Missouri. She became every bit my dad's dog as mine. We saw her frequently, any time we saw my parents, and each time, we had something new to offer.

A new baby. A new cat — a neighbor's Maine Coon named Jimmy, who decided he wanted to adopt us and became a member of our family. Then a new house and a new apartment to accommodate our newly divorced family arrangement.

In the summer of 2017, that summer when all we could talk about was the upcoming eclipse, Shiva was struggling to get up and down the stairs of their 1920s home. She was already 14 by then, old for a dog of her size.

My mom was overwhelmed with all the pending losses: My grandmother and my dad were dying, and Shiva wasn't far behind.

I hadn't missed having a dog during those years, but when this bereavement season came upon us, I knew it was time to take the baton.

I was visiting Missouri over the week of the eclipse, and on the way home from that trip, Shiva came with me.

I knew I had just signed up to be with her for whatever the last part of her life looked like. I thought she'd live maybe two months, a year tops.

But the months, and then years, passed. Shuffling turned into hobbling, and she didn't even try to pick up those big sticks anymore, but she held on.

After my grandmother died, we made a few trips back to Missouri with her, lifting her in and out of the car at each pit stop. Seeing his old dog lifted my dad's spirits, especially when he was in hospice care, and although he was at the end of his life, we also talked about the end of her life. He made sure I knew that whenever I decided it was time to put her down that I'd be making the right decision. He asked if I could keep her collar — the same blue and white flowered one she always wore — so it could hang in the basement next to Bernie's.

We buried his ashes on an icy, sun-filled February day in 2018. Surely, her death would follow, but onward she carried, her spirit strong even as her body continued its slow decline.

She was never far from me in the house, often lifting her old bones off the floor to follow me into the other room. I would tell her to stay put because I'd be back shortly, but she couldn't hear anymore. She could feel the vibrations of a clap and could spot a cat across the street, but could no longer muster the energy to run.

In the months after my dad died, Shiva and I took lots of walks. Taking the time to immerse myself in nature became a conscious act of touching in with my grief. Walking her was often the prompt I needed to get up, get out, and go soak up a sunset and inhale a big breath of air to remind me that I was still very much alive.

I kept thinking she wouldn't wake up, maybe on his birthday or his death day, or my parents' anniversary. Some special day that would help me feel like she was choosing to go out on a meaningful day.

Then the pandemic came and every day felt both meaningful and the same, and she kept waking up.

Just a few days before everything started shutting down in March, our cat, that big furball who merely tolerated that we'd brought a new pet into his domicile a few years earlier, didn't wake up from a nap on one of the last days that the kids went to school. The kids were the ones who found him, and the tears poured once the shock wore off. I'd never carried a dead animal before, but it had to be done, and I was the one who had to do it.

It was a fitting start to this tumultuous season. An unexpected loss. An act of courage. A waterfall of emotion. A new normal.

Shiva hated to be in the house by herself, and the quarantine offered us the gift of time with her. Week after week, month after month, she rarely had a moment without one of her beloved humans nearby.

When it became clear that her quality of life was declining and she wasn't dying on her own, "her time" became a constant thought. I didn't want her to suffer, but I didn't want to suffer knowing I made the call too soon. It was the inner battle my dad was trying to save me from, but preparing myself to call the vet was an important part of this particular grief journey. I needed the extra time, too.

Earlier in the month, all the energy around this decision, this loss, these losses started to flow together. The weather turned cooler and rains softened the soil. Frank's house had become a place where the kids felt at home. The fall equinox ushered in a new season around us and a new season within us. It was time.

The kids spent extra time scratching her neck and kissing her forehead. They were the ones who asked if we could all be with her when she passed. Because of the coronavirus, most vets aren't allowing families to be present during in-office euthanasia.

Their courage fed mine, and I called to set up an at-home appointment.

The night before, we dug her grave and had a fire so we'd have extra ashes to help her body return to the earth. I listened to my dad's favorite music while I shoveled dirt. I thought about how much has changed in these 15 years since she came into my life. How I never could have imagined that this sweet dog would have outlived my father and that my teen and tween would have the strength and wisdom to know that how you die is a reflection of how you live.

Having the serenity to accept the things I cannot change soothed my soul during the loss of my dad, grandmother, and friend, and having the courage to change the things I could meant making a decision to give Shiva a peaceful death in a place she knew with people she loved.

Grief and loss can seem like something that is always out of our control, but how we choose to respond to it and work with it is very much in our hands.

In The Wild Edge of Sorrow, Francis Weller writes that grief is the pilgrimage to the soul:

"When we are able to see times of loss as inevitable and, in a very real way, necessary, we are able to engage these moments and cultivate the art of living well, of metabolizing suffering into something beautiful and ultimately sacred."

A million people have died of COVID-19 this year, 200,000 and counting in the U.S. If you don't know someone who has died from this modern plague, you're likely grieving something else. A workplace. A sense of safety when you're with your family. Rituals. Routine. Hugs.

Add in the grief around racism and climate change and colonialism and dysfunctional family legacies, and we're looking at a mountain of grief that we can no longer walk around.

The loss of a pet — or two — during this time of collective crisis is both small and significant. Honoring the role that animals play in our lives is important. Honoring ourselves as we walk through our own changing seasons is, too.

"Sorrow is a sustained note in the song of being alive," Weller writes in that grief book that I've grown to love so much. "There is some strange intimacy between grief and aliveness, some sacred exchange between what seems unbearable and what is most exquisitely alive."

Grief and happiness, death and life, are not fixed places. Sitting with loss might make me feel like my feet are in cement, but what if that is the feeling of my roots growing deeper? When I'm soaring on the wings of happiness, I enjoy the view but miss the texture of the ground below.

Maybe a year like this, changes like these with challenges like this, help us get more comfortable with this contradiction. Maybe our happiest moments are colored with sadness because they won't last, and our deepest joy can live alongside our greatest sorrow because they remind us of what was.

Very sweet story, Addie. Just curious how Shiva got her name. The word has a special meaning in Judaism.