New book chronicles ‘a leisurely waltz with eternity': the first untethered spacewalk

Austinite Bruce McCandless III’s new book tells the story of his space-walking dad’s famed flight and what it’s like growing up the son of an astronaut.

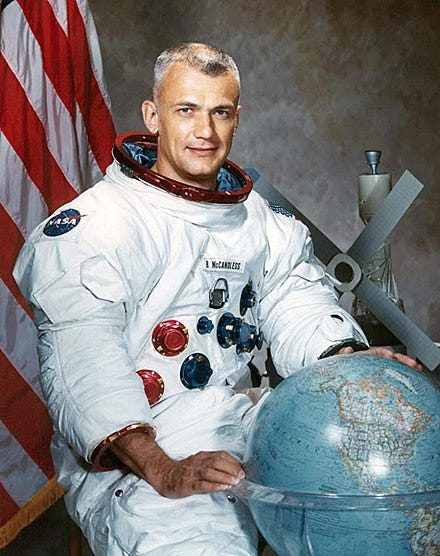

You know Bruce McCandless’ most famous moment, but you probably don’t know his name.

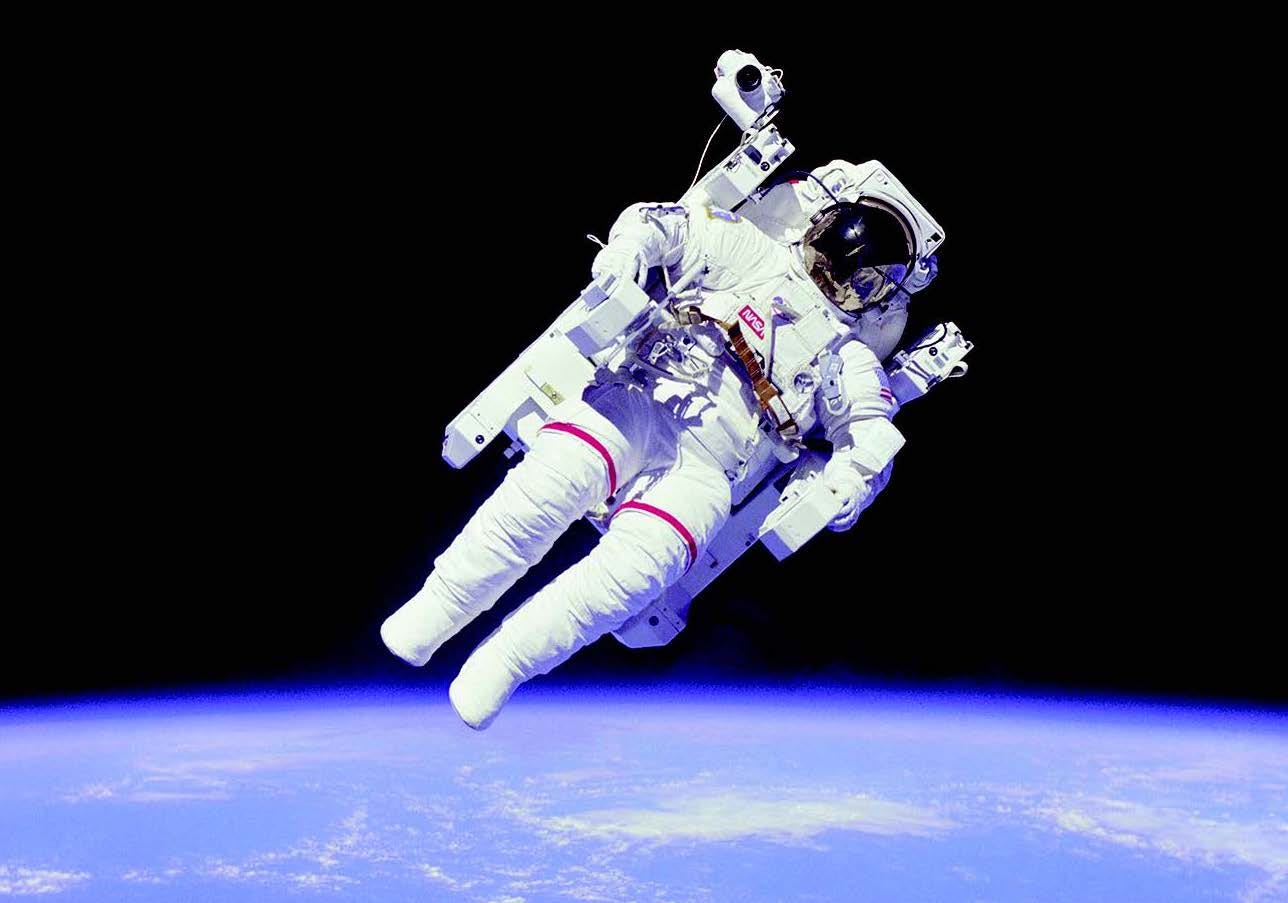

McCandless is the astronaut who, in 1984, became the first untethered astronaut in space. He’s the guy on those posters, mugs, shirts and everything else NASA could sell with the image of his “leisurely waltz with eternity,” as his son calls it in his new book, “Wonders All Around: The Incredible True Story of Astronaut Bruce McCandless II and the First Untethered Flight in Space.”

I met McCandless III, who lives in Austin with his wife Pati, for a coffee a few months ago, thanks to the introduction from a mutual friend. As we talked about losing our dads, being writers and parents and living in Austin while still dealing with COVID, his dad’s famous flight didn’t come up, but the process of writing such an epic biography of a complex, only recently passed man was something worth unpacking over coffee.

I hadn’t read the book yet, but over the next few weeks, I got to know the McCandless family in such a sweet way that I wanted to write a little about the book here to perhaps inspire you to seek out a copy of “Wonders All Around.”

As much as this is a book about space, it’s also a book about grief. And persistence. And stoicism. And masculinity and maternality.

The elder McCandless died in 2017, just a few years after losing his wife, Bernice, to cancer.

This passing of the torch from father to son left the younger McCandless inspired to take on this decades-long narrative. McCandless III sets the tone for the book with a memory of the family sitting around the dinner table at their home outside Johnson Space Center near Houston in the mid 1970s, when his dad, who joined NASA in 1966 at the age of 28, wasn’t sure he’d ever actually make it to space.

“Our dinners were somber affairs. We ate around a rectangular Formica table in the breakfast nook. Tracy and I sat on benches padded with orange vinyl cushions. Mom and Dad occupied faux-Spanish style chairs with green felt upholstery. Despite the informal, Howard Johnson’s-at-the-airport feel of the furnishings, there was a tension in the air that set in right around the time the frozen string beans started steaming. I had the feeling that my sister and I had forgotten to do something important, though I couldn’t figure out what it was, or that judgment had been rendered on us and we’d been found guilty of … something — again, it was unclear what. Horseplay was prohibited. The TV and all sources of music or other frivolity were turned off, and singing was strictly forbidden. The only sound came from the aquarium pump. My father had a 100-gallon tank along the wall behind his chair. Sometimes the big plecostomus would attach itself by its mouth to the glass facing us, and I imagined it sucking all the oxygen out of the room.”

Imagining what it must have been like to require oxygen to survive, not in outer space but in the living room with your family, sets up the story of the McCandless ancestors, including a guy who was killed by Wild Bill Hickok and the author’s grandfather, who was an admiral in the U.S. Navy.

No pressure, Bruce.

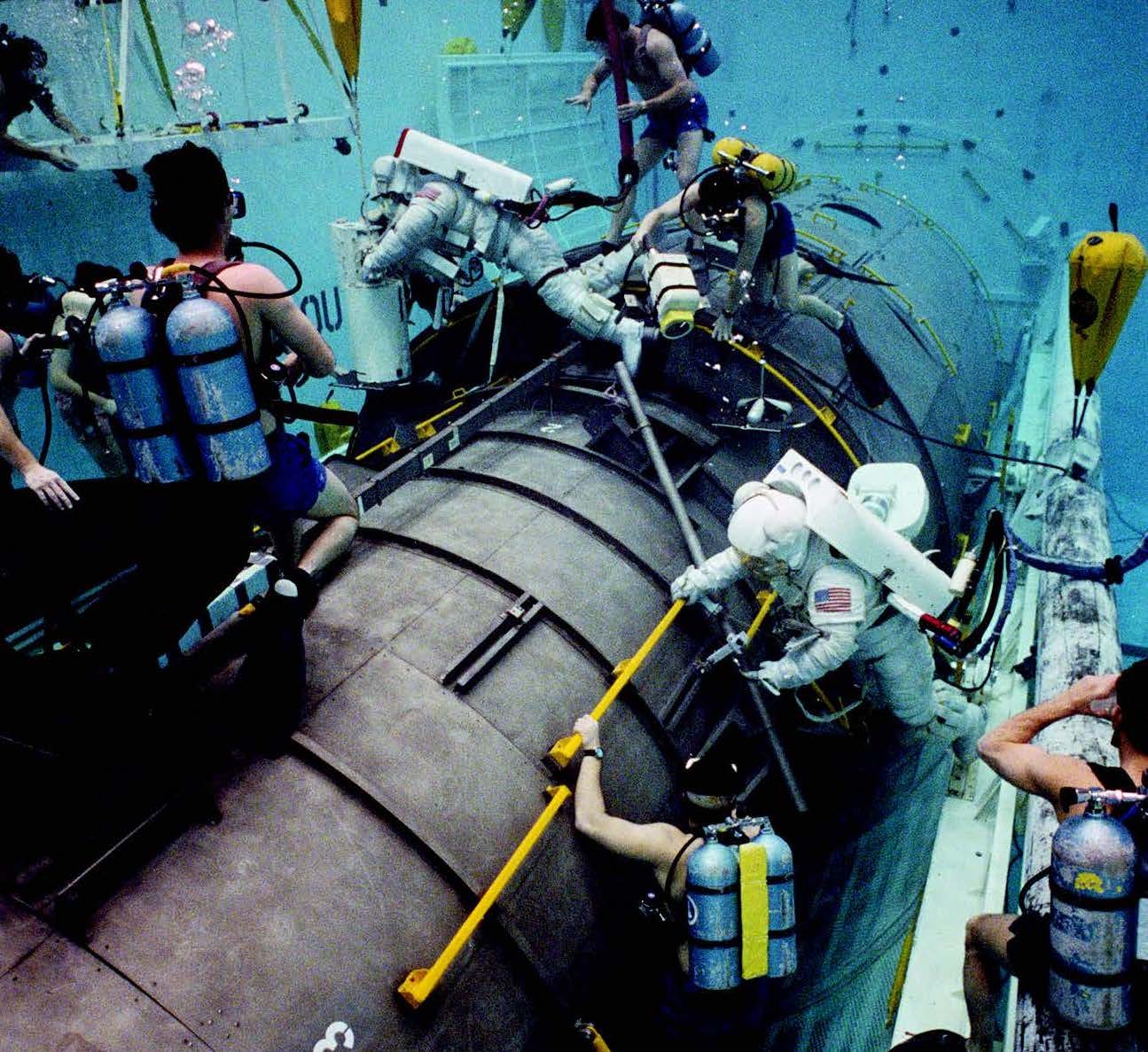

It was fascinating to read about the 18 years that Bruce McCandless II worked for NASA before he finally had his first flight, which debuted the Manned Maneuvering Unit, a jet-fueled backpack that he and Ed Whitsett Jr. spent so many years developing. (That’s the joystick-controlled machine he’s wearing in that mind-bending poster that hung on millions of Americans’ walls over the following decade.)

The author McCandless has the unenviable task of trying to put into words what that flight must have felt like. His dad flew 150 feet away from the shuttle Challenger, which would, of course, break into a million little pieces just a few years later.

When President Reagan called the shuttle to congratulate the astronauts that day in 1984, the command center set up a demonstration space walk to give the president a live view of McCandless through the shuttle window.

The only problem was, there wasn’t much fuel left. McCandless went out anyway, trying to stay within 10-15 feet of the spacecraft. He got into position and turned off the unit to preserve propellant. After the president said a few words and the video switched off, McCandless turned on the unit and “looked for the closest piece of the orbiter, pointed at it, put the hand controller in +X (and) got a sort of sighing noise as it accelerated in that direction.” He ran out of fuel just as he grabbed onto a rail on the orbiter. Hand over hand, he brought himself back to the donning station.

It’s that kind of suspense that made this book so thrilling to read.

There’s space tension like when McCandless is operating as CAPCOM, the only person talking to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin while they are walking on the surface of the moon, and his commander wants him to break protocol and call them back early, even though there are no signs of distress.

The book is also so touching. I cried while reading about the declining health of Bernice, who survived so many astronaut wife struggles over the years and at the end of her life remained a loving partner and mother.

It’s easy to forget that McCandless II had an entirely other memorable historic moment — launching the Hubble Space Telescope in 1990 — and this one seems to have struck an even deeper chord with McCandless III.

The Hubble launch was McCandless’ second and final flight. He was 52 and had worked at NASA for 24 years.

McCandless II spends the last chapters of the book making a compelling case that his dad’s work to fix and update the Hubble are among the greatest achievements to science. He continued to work on Hubble for another two decades after retiring from NASA through his work at Lockheed Martin.

He was the “nuts, bolts, screws, and wires guy,” the auto mechanic rather than the scientist, who kept the telescope going 340 miles above Earth for more than twice its life expectancy. The Hubble has been cited in more than 18,000 scientific papers and has revealed countless secrets and unsolved mysteries from around the universe and beyond.

“The size, shape, and sheer spectral weirdness of the images boggle the imagination and make prophets and dreamers of us all,” McCandless writes toward the end of “Wonders All Around. “Some of us pay therapists to tell us we’re important and unique. Then we check in with Hubble so the satellite can inform us just how galactically marginal we all are. The truth is somewhere in the middle.”

What a beautiful reminder.

___________________________________________

I hope everyone is enjoying this sunny Sunday! I’m launching “Class Reunion: The Podcast” in less than two weeks, so I’ve been spending a lot of time getting the trailer and first episodes ready.

I’ll share a separate update about the podcast next week, but in the meantime, head over to patreon.com/classreunionpodcast if you want to be the first to know when the first episodes are released.

Thank you, as always, for your Patreon support! Your newsletter subscriptions help me make a monthly donation to a nonprofit, and this month, I’m giving to Parasol Patrol, which provides visibility and support at Pride events across the country.