Spending Juneteenth with the one and only George Washington Carver

I knew peanuts about this American icon before visiting his birthplace in Southwest Missouri earlier this week.

George Washington Carver was 12 years old when he set out in the world.

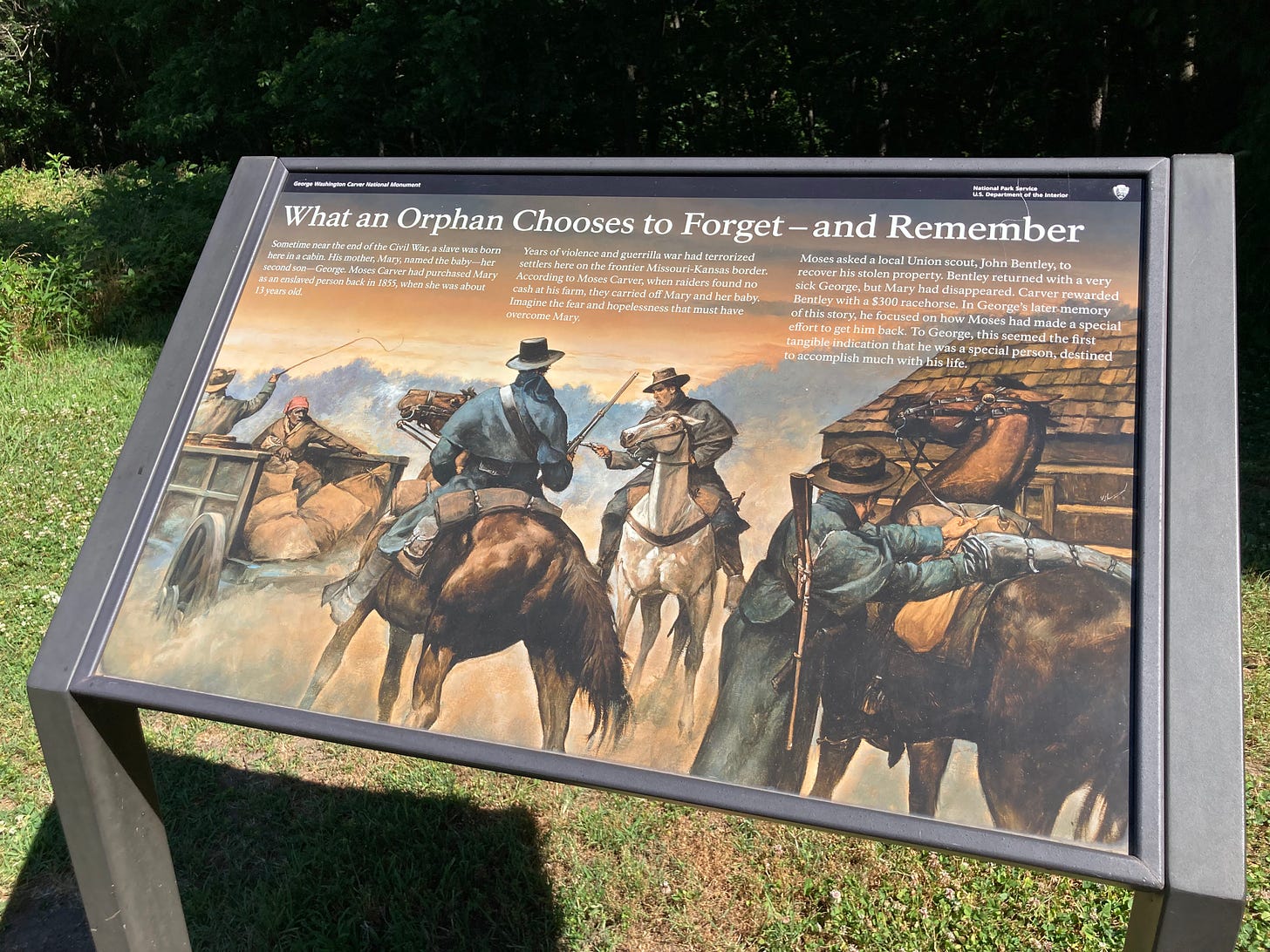

He’d been born sometime during 1864, the year before the end of the Civil War, to a woman who was enslaved on a farm near what is now Diamond, Missouri.

As a baby, he was kidnapped along with his mother, and the man who owned them sent out a search party. They only found the baby, whom Moses Carver and his wife, Susan, raised in a cabin on a wooded parcel of land that, in 1943, became the first national monument to honor a Black person.

Diamond is about 40 miles west of my Southwest Missouri hometown, and although I knew his birthplace and a national monument were nearby, I never went as a child or young adult. Or grown adult.

But that changed on Monday, when my mom and I visited the museum, which was open even though it was the second federally recognized Juneteenth. (Listen, I’ve never understood how bank holidays work.)

I was expecting to learn about Carver’s impact on agriculture science with perhaps a little racial reckoning on the side, but I left in utter amazement. This man understood some things about persistence, reverence, curiosity and being a trusted servant of a higher power that I needed to hear.

First, some backstory: “Carver’s George” became “George Carver” when he finally started attending school in nearby Neosho, whose “colored school” is marking its 150th anniversary this year. (It’s worth noting that Carver never signed his own name with “Washington” spelled out. He picked “W” as a middle initial to differentiate himself from another George Carver in school.)

After starting his education in Neosho, Carver set out on his own — on foot — just a few years later, moving from town to town in Kansas in pursuit of a meal, something new to learn or, after watching several lynchings in these sundown towns, simply a safe place to sleep.

He eventually landed at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, where he studied art and piano. (He won an honorable mention at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair for a painting that is now housed at the Carver Museum in Tuskegee.)

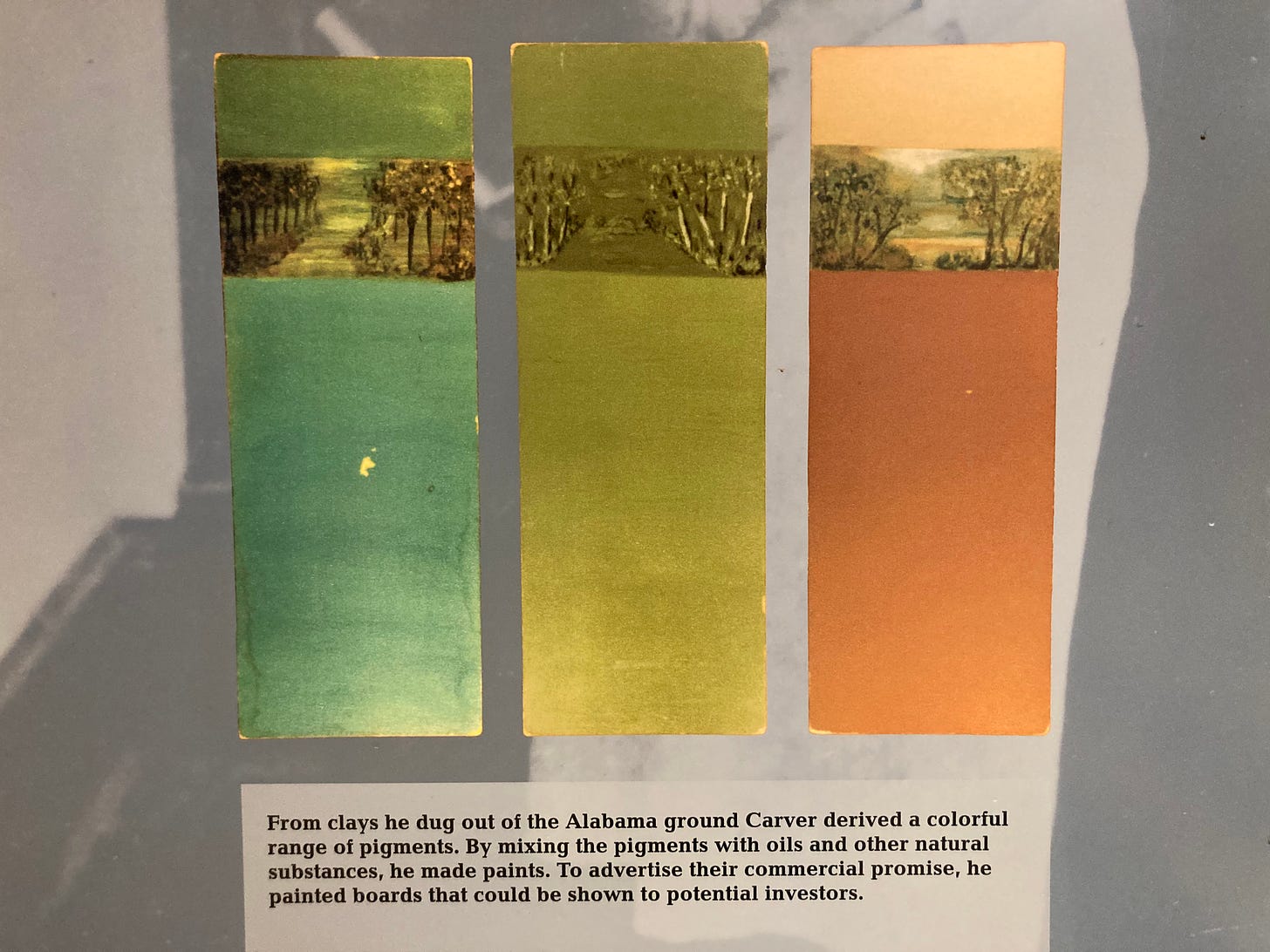

Although art was his passion, he felt that God was directing him to use his creativity in the sciences because more people would benefit from his work. One of his art teachers encouraged him to study botany at Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames, where he became the school’s first Black graduate, earning both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in science.

In 1896, he started what became a 47-year career at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he developed scientific solutions that would specifically help Black Americans, many of whom were sharecroppers trying to grow cotton on depleted southern soil.

"I come here solely for the benefit of my people," he told Tuskegee when he first arrived.

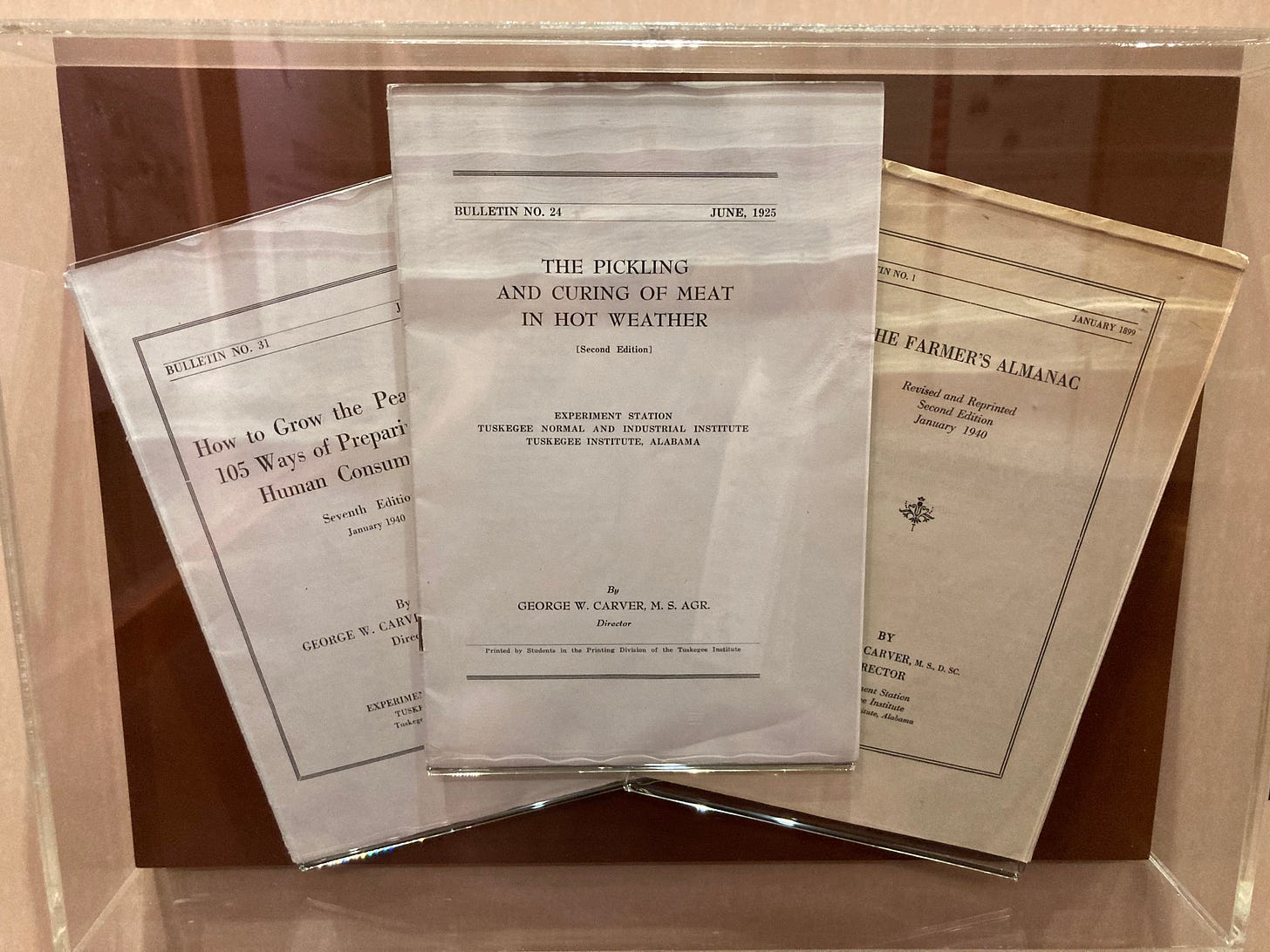

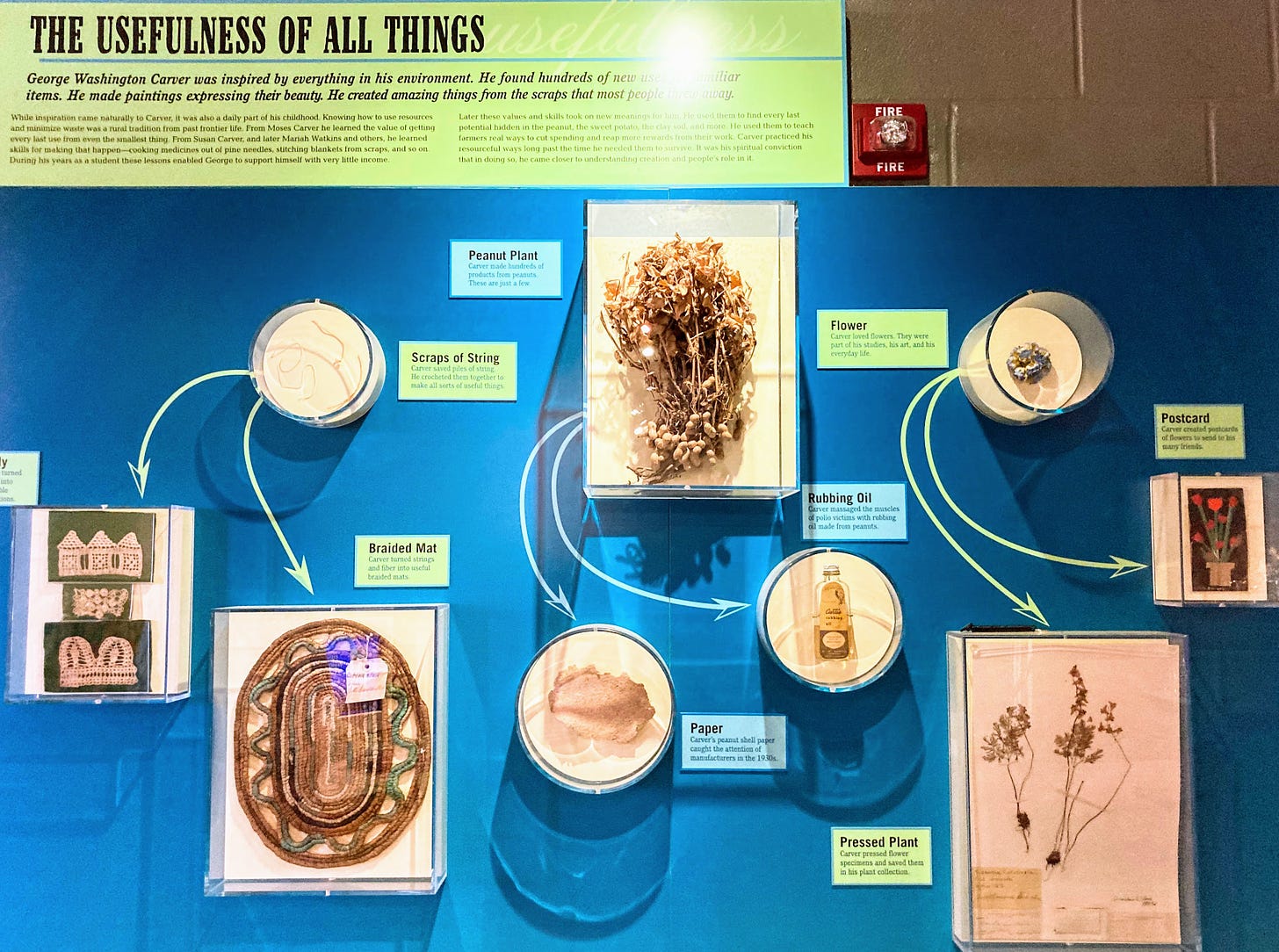

Carver knew it wasn’t enough to tell farmers to stop growing cotton. He needed to find a way to persuade them to try these cover crops — like peanuts, yes, and sweet potatoes and soybeans and corn. That’s why he made paper out of peanut shells and dinner mints out of sweet potatoes.

It wasn’t for the novelty. Or the fame. Or the money.

He only filed for three patents in his life: one for a pomade made from peanuts and another two for making pigments and stains out of clay so that people could create art without having to buy paint.

This is where I felt my heart shift from feeling curious about this person to being transformed by his story.

As a boy, he knew he had a knack with plants, but throughout his life, he infused his art into his botanical study. He knitted and crocheted using natural threads he wove from the peanut fibers. He developed a teaching wagon that would creatively display the information the scientists wants to convey to farmers during educational tours in rural areas.

"Learn to do common things uncommonly well; we must always keep in mind that anything that helps fill a dinner pail is valuable."

Carver was a man obsessed with finding utility and beauty in everything. He refused to let anything go to waste. He set up his first lab at Tuskegee using discarded junk he found in the landfill.

"I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting system, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in."

He didn’t see any tension between faith and field work. "Without God to draw aside the curtain, I would be helpless."

Carver never married. Never had any children. Never strayed from his purpose: “to help the man farthest down.”

When I was at the museum on Monday, I read that quote and it made me think of something Glennon Doyle said recently about feminism. “I’m on the side of whoever is getting the most fucked.”

America’s favorite scientist wouldn’t have approved of the language, but he understood the sentiment.

He was an orphaned, unmarried Black man pursuing an education and a life of meaning during the Jim Crow era, and yet when he spoke, people listened.

Would people have listened to him today?

When the monument in Diamond opened in 1953, more than 2,000 people showed up to celebrate a man whose scientific research — much of which farmers continue to rely on, including crop rotation, organic fertilizers and deep planting — had transformed agriculture.

But in the 21st century, I think his legacy transcends the scientific discoveries, and I wouldn’t have had any appreciation for it if we hadn’t gone out of our way to stop by this museum earlier this week.

The national monument is hosting Carver Day on July 9 to celebrate its 79th birthday, and I imagine there will be even more festivities next summer for the 80th, but if you are in Bentonville, Branson, Springfield or simply passing through on Interstate 44, take the detour to the national monument.

I spent decades thinking “I should go there one day,” and I’m glad I didn’t let one more day pass without knowing about this incredible, multi-dimensional human whose wholeness, whose resiliency, whose dedication to making a difference and to learning more about the world around them is something I *really* needed to immerse myself in.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorite Carver quotes I’ll be keeping close:

"My work, my life, must be in the spirit of a little child seeking only to know the truth and follow it."

And I thought his legacy was peanuts.

Thanks for reading and subscribing! I hope that something in this post sticks with you as we all consider what the little child inside of us is seeking.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this week’s posts about Title IX and George Washington Carver. I’m so grateful to get to share pieces like this — it still feels surreal to get to share columns directly with readers through this not-so-new-but-still-novel platform.

Thank you for your support! Tell a friend if you’ve enjoyed subscribing. Word of mouth is the best advertising, after all.

Addie

Love this! Love the ending. “…just peanuts.” And Carver’s quote for all of us to live by.

Thank you!

I feel proud that southwest Missouri is home to this monument. Thanks for sharing the legacy and lessons from this amazing and humble man.