The glory of being a 'happily contaminated' American

A night with culinary historian Michael Twitty, who knows what butters his bread this July Fourth.

If you’re firing up the grill this week to celebrate Independence Day, pause for a moment to think about this:

Every Black rebellion started with a barbecue.

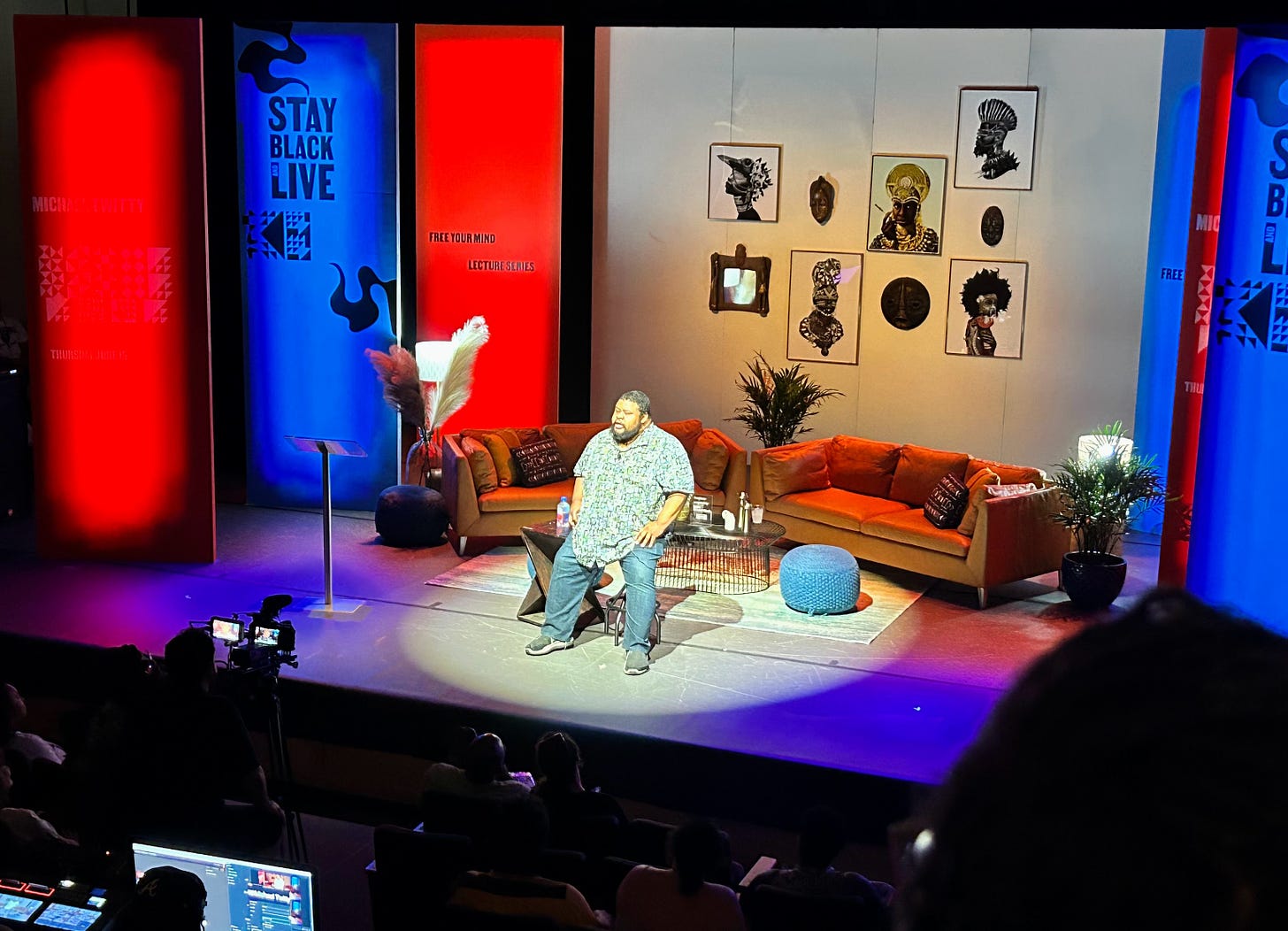

“Nat Turner, Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, the Haitian revolution. All of these started with the ceremonial act of sacrifice and a communal feast where the memo spread that it’s time to fight,” the James Beard-winning culinary historian Michael Twitty told an audience of more than 100 last month at the George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center in Austin.

“It makes sense that it’s our freedom food.”

When Twitty says “our,” he means “our.” All Americans. Not just Black Americans.

Because he’s not simply a Black American. Or a gay American. Or a Jewish American. “I’m an Ashanti American, an Igbo American, a Congolese American, a Malagasy American, a Trinidadian American.”

I met Twitty, who is now a National Geographic Emerging Explorer, more than a decade ago through Twitter, when he was making the leap from being a seventh grade teacher at a Hebrew school to a full-time historic interpreter.

This was before he became known as the author of “The Cooking Gene” and “Koshersoul,” but he was already well on his way to becoming one of the country’s foremost experts on Black foodways.

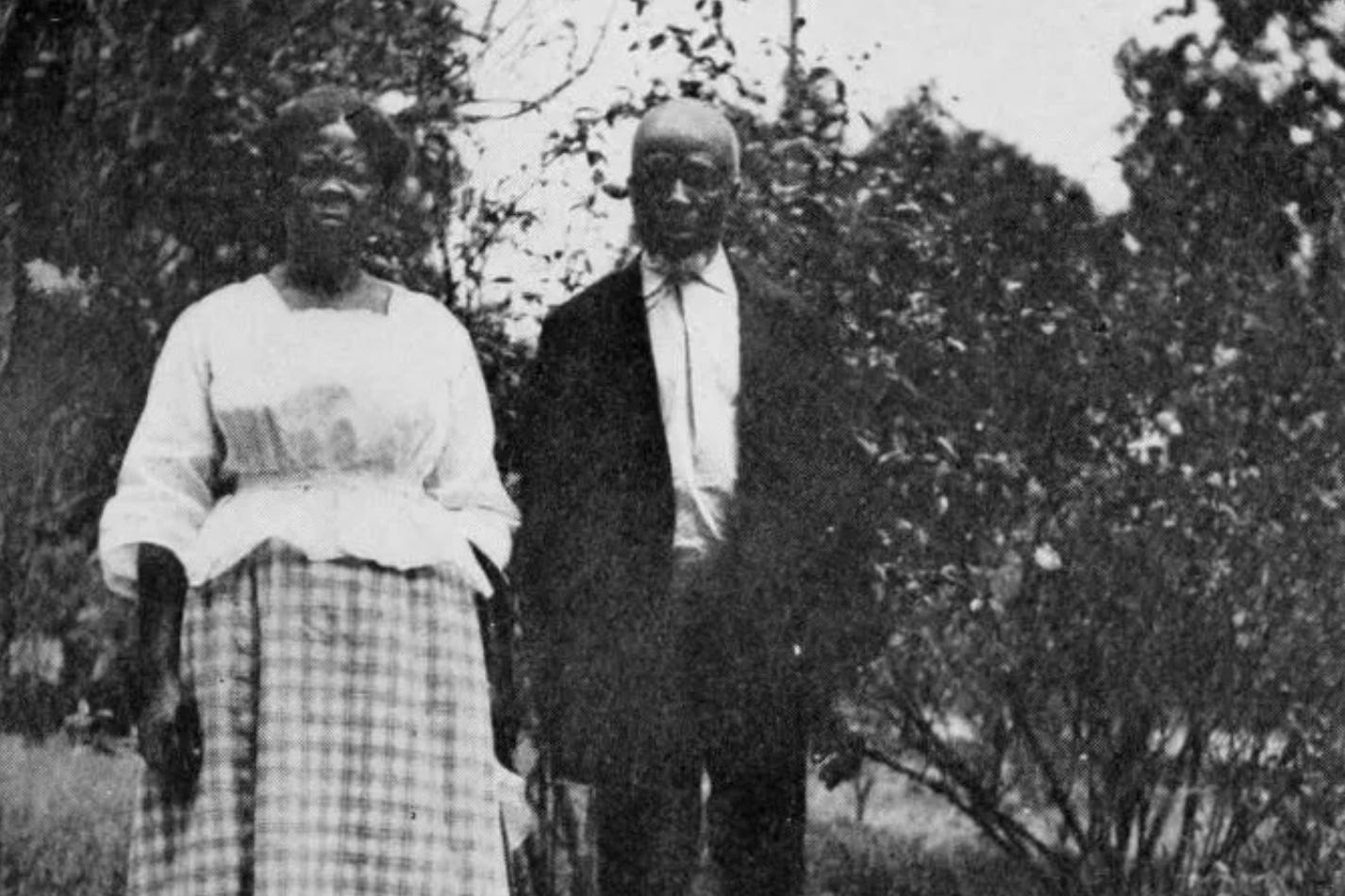

At plantations across the South and in an online Masterclass, he uses food and cooking to explain what life was like for enslaved people and how it evolved over the next 400 years and how everyone can engage their own ancestral lineage to learn more about themselves and where they live.

“I didn’t like the first time I put on historical clothes. I didn’t like how I felt because I thought, ‘This could have been me,’ but a debt was paid so that it wasn’t me,” he said in the lecture that was part of the Carver Center’s Juneteenth programming. “I put the clothes on and go do the work, but I’m not a reenactor. I interpret slavery because it has to be in the hands of the descendants to tell our story.”

Twitty argues that all Americans, particularly white Americans, have adopted Black, indigenous and Latino foodways as their own. “For all the talk of our Anglo-Saxon heritage [which he also shares], when was the last time you ate jellied eels or yorkshires or toad in the hole or spotted dick?”

But American food that we eat today, from sweet potato casserole at Thanksgiving to Rice-a-Roni on a Tuesday night, reveal relationships that won’t get taught unless we fight for them to get taught.

“Without the global south, humanity would starve,” he said. “Our collective mama is Black.”

Twitty talked about the name “soul food” as a nod to the intuition that lives in our gut, alongside the bacteria that keeps us alive. “Our ancestors live there, too.”

Once he started a dialogue with these ancestors, he said he couldn’t ignore their howling. “But there are boundaries,” he joked. “There are times when I have to say, ‘I’m off the clock right now’.”

Over the past decade, Twitty has met hundreds of cousins across the globe, from white Texans he met through Ancestry.com to Congolese cousins who call him “Mr. Cooking Gene.”

He has made nine trips to Africa, each one a kind of rebirth and a rediscovery of what it means to be American.

“If you’re an American, you’re multicultural by default, and if that’s not what you want to be, then you are forfeiting the glory of being an American.”

— Michael Twitty

To be American is to be “happily contaminated” with every culture that makes up who we are.

One myth he dispels again and again is that the people who were enslaved ate whatever was left from the slaveholder’s house. “You’re telling me that five white people gave their leftovers to the 100 people working in the field? It didn’t work that way.”

Correcting the history of soul food means acknowledging that Black Americans had a sense of autonomy and self-ownership from the beginning. They were growing their own food and raising their own livestock not only to feed themselves but to keep their cultural traditions alive, from generation to generation.

One common thread shared by many Black and brown families is cooking enough food to feed as many folks as they could. “We’re accustomed to cooking for the neighbor, the cousins, the auntie, the abuela, and everything got eaten, because we were feeding people who had run out of energy or the resources or were alone,” he said.

“What comes out of the cast iron skillet solves more problems than hunger.”

Twitty’s books chronicle in great detail the arrival and migration of enslaved people from the colonial coast through Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and, finally, Texas, which has the highest population of Black people today.

By 1750, a majority of Black people in America were born in the U.S., but the slave trade continued for another 110 years.

“Every black family has ancestors who showed up early and those who showed up at the tail end,” he said. “Do you know how alienating that must have been to show up here at the very tail end of things and to be surrounded by people who looked like you but you don’t understand why they are so different?”

This was as late as 1860, when the last ship carrying people who were forced into an immigrant story they didn’t sign up for arrived in America. “Not only were they in exile forever from their home, but they were caught up in something that they thought was fading away.”

He let the words hang in the quiet theater.

As a longtime educator, Twitty is one of the most engaging speakers I’ve ever heard speak about food and food history and how it has shaped American culture.

He relishes working with young people who are often quick to make connections between the historical stories he tells with what they have seen in their short lives.

“I tell them: ‘Young queen, young king, I want you to know, like somebody told me, you come from something, and you’re going to leave something that is so glorious and divine.’ Like [the poet] Nikki Giovanni said, ‘Even your errors are correct’.”

In an era of devastating divisions, Twitty doesn’t use food as a way to separate anyone from anyone else. “Let’s look for the foodways that our ancestors shared. We are part of the same dysfunctional Southern family, and we have co-created the world we live in for centuries. This is a two way street, and to some people, that feels like oppression.”

Twitty encouraged all of us to find those parts of ourselves that were almost lost. “Let me look to these people to help me find my way.”

These people, known and unknown, who came before. Let the past inform your present and shape your future.

He used a line that I’ll never forget: “You know, when the ancestors are on your board of directors, you know what butters your bread.”

What an absolute delight it was to hear Michael speak last month.

I’ve attended number of his lectures over the years, but this time, I brought my 16-year-old, who has been studying culinary arts these past few years of high school.

After the event was over, we quickly turned into two chatterboxes in the car on the way home. Julian has watched my own pivot toward ancestral healing over the past decade, especially with that trip to Sweden in 2016 and now my work as a tarot card reader and with this newsletter.

Having heard the word “ancestor” more than most teenagers, he is developing his own ideas about what kind of relationship he wants to have with the whole concept.

It was special to get to be with him while we heard someone else’s perspective on it.

We both agreed that the concept of the “happily contaminated American” was something we needed to hear, especially as we approached the Juneteenth and July Fourth holidays.

I thought you all might enjoy learning about it, too.

So, no matter what you are or aren’t doing this week to mark your American-ness, I hope this piece brings some new ideas to your dinnertime conversations.

Forever buttering her bread,

Addie

P.S. I hope you all are enjoying your zines! I sent out more than 100 copies to subscribers in more than 15 states (and one all the way to Prague!). I am still missing a few addresses, but I’ll be tracking down those folks over the next week.

And thank you to all the new folks who have joined the paid subscriber community! I hope you enjoyed this piece and all the stories headed your way. The next zine will be published in November/December.

I'm an addicted fiction eater/reader Addie, so your zine has its place beside my bed, but it hasn't had more than a quick surprised (it's so bright and snazzy and not at all like a 'book' or even magazine (which I dont read much of, except AARP features and movie/tv recommendations.) Hope you forgive my truth telling and don't take personally a life time of choices to READ NOVELS, always and primarily my favorite source of pleasure. Yet I choose to stay subscriber to your writing and hopefully will continue to grow in knowledge and wisdom as I slip in your Zine and your blogs.

Thanks, Addie.