What happens when a lake vanishes?

Spend a few days on Lake Buchanan, and you'll think about impermanence, too.

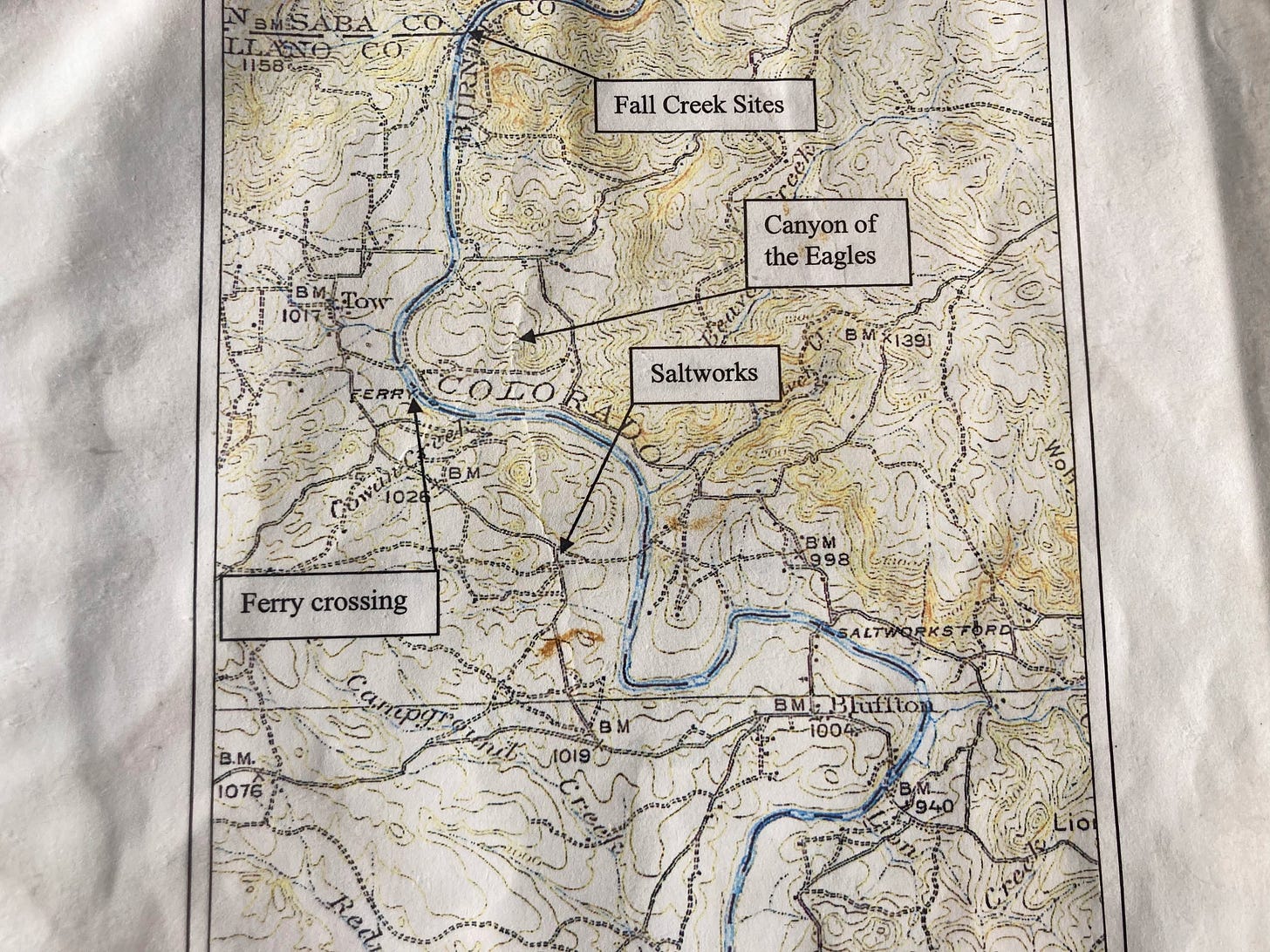

To get to the spot where Fall Creek hits Lake Buchanan, you have to pass through a graveyard of trees.

Last week, I was visiting the largest of the Highland Lakes on the Vanishing Texas River Cruise, a boating tour company that has seen the lake’s highs and lows — literally — over the past 40 years.

Right now, the water is up at this reservoir that provides water to more than a million people in Central Texas, but if you’ve lived here long enough, it’s impossible not to think about those years when droughts drop the lake so low that the settlements flooded to create it reveal themselves again.

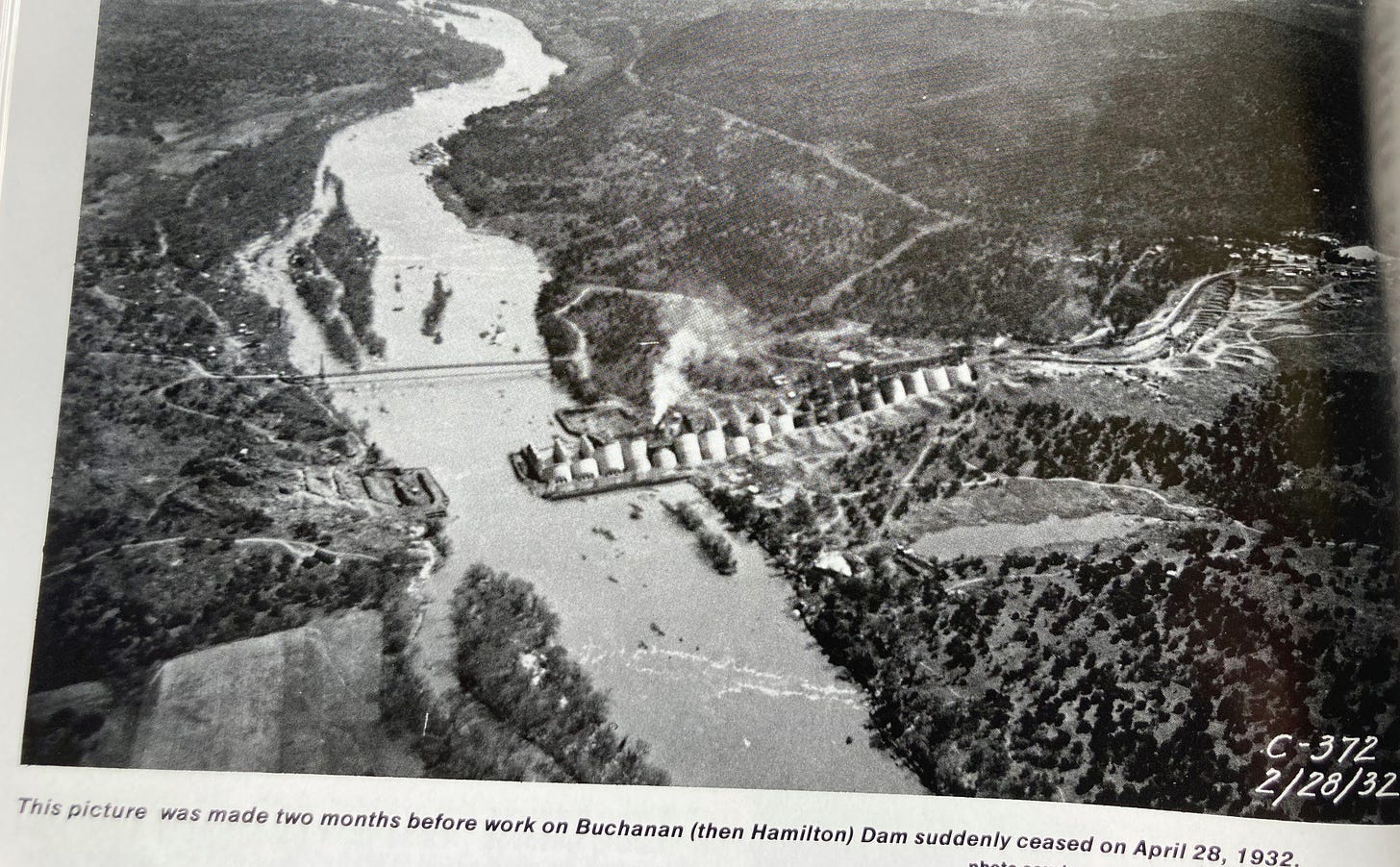

Back in 2011 or 2012, I rode on this very boat with my toddler in tow to see the ruins of Bluffton, a small community whose residents were displaced in the 1930s when the Lower Colorado River Authority started building the dam between Burnet and Llano.

That was my first drought. Before those dry, hot years, I’d never paid attention to lake levels. I’d never seen the bottom of the Pedernales River.

I’d never wondered how bad it might get.

I don’t live anywhere near these lakes, but the shallowing waters gave me a sense of doom I’d never experienced before: What if the water didn’t return?

As I write this on a sunny spring Sunday morning, Lake Buchanan is 87 percent full. Lake Travis is 67 percent.

The water did return. I remember those rainy weeks in 2014 and 2015, when the Colorado River finally flowed heavily enough to revive those shrinking bodies. To bring life back to the communities that depend on the lake for more than recreation.

We’ve had a nice run of years with full or nearly full lakes, but we haven’t had much rain this spring, and I hear nerves in people’s voices when they talk about the weather: Are we going to get a Memorial Day deluge? Or is this the beginning of another water drop for the record books?

Last week, as a tourist in my own backyard, each time the conversation returned to drought, I remembered that persistent dread that we lived with a decade ago.

I felt a little of that dread returning.

If the lakes can drop low enough that 30-foot trees grow on what used to be the lake bottom, they can drop that low again.

Our tour guide, Tim Mohan, who has been leading boat rides up the lake and the Colorado River for almost 20 years, says that those trees leafed out the first year after the water returned.

He’s lived through enough droughts to know that they always end.

At least they have always ended.

But scientists say the Lake Powell and Lake Mead, which capture water from the other Colorado River, will never fill again.

Could that happen here?

Mohan thinks the water will return. He thinks those trees have decayed enough that they’ll wash away during the next flood, as if it is a certainty.

Is anything certain? What else will change during the next flood? What will happen to this area between now and then?

Since we can’t predict the future, let’s look to the past:

Some facts I’d forgotten about Lake Buchanan (and maybe you had, too): When the Buchanan Dam was finally finished in 1937, the LCRA thought it would take 10 years to fill. But the slow creep of the river filling this Hill Country basin didn’t stay slow for long. A rainy summer in 1938 topped off the lake in just 15 months.

But by 1952, the town of Bluffton revealed itself again for the first time, thanks to an epic drought whose record water level lows still haven’t been broken — not even in 2014.

I can only imagine what a surprise it was in the early 1950s when people who still held memories of Bluffton heard that its ruins were resurfacing. Those people had already seen Lake Buchanan fill once, and in the years that followed, they would watch it fill again.

But once you’ve seen a lake drop this low, I don’t think you forget it.

But plenty of people in the Marble Falls area haven’t seen the lake this low. The whole region is experiencing what they call “the Austin creep,” and it’s easy to see those changes: subdivisions with rolling hills of rooftops, construction to expand the highways, billboards to advertise the businesses opening to cater to residents and tourists.

What will it take to get all those folks to understand just how volatile our water supply is? What will it take to ensure the safety of people who don’t fit in the white/straight/cisgender boxes? Will environmental pressures force us to face the undeniable damage that settlers brought to Texas as they laid the foundation for the society that we live in today?

What will it take to correct the error of erasing Lipan Apaches, Comanches and Tonkawa from this history?

During my weeklong visit to Burnet County, only one person gave a land acknowledgment to name the tribes who called this place home and whose history has become something of a footnote in what is now a white, conservative area of Texas.

But there are clues to this history if you listen closely. On the boat tour, we found out that a rock near Fall Creek is called Ceremony Rock and was a sacred place for Native folks who lived in the area. (I chose not to photograph the falls with the rock in honor of those who have used or might still use it for ceremonial purposes.)

The lake itself has become something sacred for people who live in the area.

It’s amazing to think that just 85 years ago, this grand body of water was just an idea.

As we cruised this feat of human engineering just after sunrise on Thursday morning, I had my own sacred moment as I thought about those trees that will one day wash down the river and the people whose homes were lost to this lake and whose names we’ll never know:

No matter how persistent something is — a drought, a real estate boom, a 2-mile-long dam — nothing is permanent.

Happy April! These last few weeks have been busy busy with a couple of freelance stories, a spring garden that needed planting and this press trip to Burnet County.

It was such a pleasure to explore this area with visiting journalists, most of whom had never seen this part of the Hill Country. I saw parts of it I never knew existed and revisited experiences, like the river cruise featured in today’s dispatch.

A little backstory here: I couldn’t take these media trips when I was a staffwriter at the newspaper, and I feel so grateful to be able to take them now, not so I can churn out some carbon copy of a travel story but because these trips allow me to write about new (and not-so-new) places through the Feminist Kitchen lens.

Just as food writing is more than recipes, travel writing is about so much more than where to go and what to do. My favorite travel stories add context so people can learn about the people, history and dynamism of a place, as well as the humanity that we all bring with us everywhere we go.

So…speaking of writing…I have some fun news to share: The Feminist Kitchen is nominated for a Best of Austin 2022 Award from the Austin Chronicle!

I was so honored to see my name pop up on the Best Food Writer list, which feels a little odd because I don’t feel quite like a food writer any more, but I’d be honored to receive your vote. (The deadline is April 18!)

I say this every week, but your support of this newsletter means so much to me and all the other independent journalists out there carving out a new home for themselves on the internet. So many folks are leaving traditional media jobs, and platforms like Substack allow us to continue writing and sharing content directly with readers.

It’s been a game-changer for this writer. And it couldn’t happen without you. So thank you. Again. ❤️

Addie

Congratulations on the nominations!

We've succeeded in ruining the planet. Pure and simple :-(